Cómo la SB 1383 ha impactado a los bancos de alimentos de California

marzo 27, 2025

No ofrecemos comida. Aquí es donde puedes Encuentre comida gratis aquí.

No distribuimos alimentos. Encuentre comida gratis aquí.

我們不直接提供食物,但我們能幫助您找尋食物。

In 2022, California began implementing its first-in-the-nation Short-Lived Climate Pollution Reduction Strategy, otherwise known as Senate Bill (SB) 1383, which aims to keep organic waste out of landfills, where it emits harmful methane gas (a major source of climate pollution). The law now requires that inedible organic waste – such as food scraps and yard waste – be recycled or composted, and that surplus, unsold food that is still safe to eat be recovered and used to feed people.

CalRecycle, the agency that enforces SB 1383, estimates that 2.5 billion meals worth of edible food ends up in landfills each year. To help reduce this, large food businesses such as supermarkets and wholesalers are now required under the law to donate their excess edible food to food recovery organizations (FROs), such as food banks.

In 2023, over 200,000 tons of unsold food was recovered by FROs in California to redistribute to community members, with the intention of helping communities address food security while also fighting climate change.

Yet many California food banks have found themselves faced with challenges of dealing with the extra logistical and administrative tasks required to comply with the law. On behalf of our network, we wanted to learn and document: How have food banks been impacted overall by SB 1383? Has the law helped food banks better feed their communities or advance their missions? What is working well (or not working)?

Last year, we conducted a study among our member food banks, with the goal of answering questions like these. The final report describes the study’s methodology, findings, and recommendations.

In summary, we found that since SB 1383 went into effect:

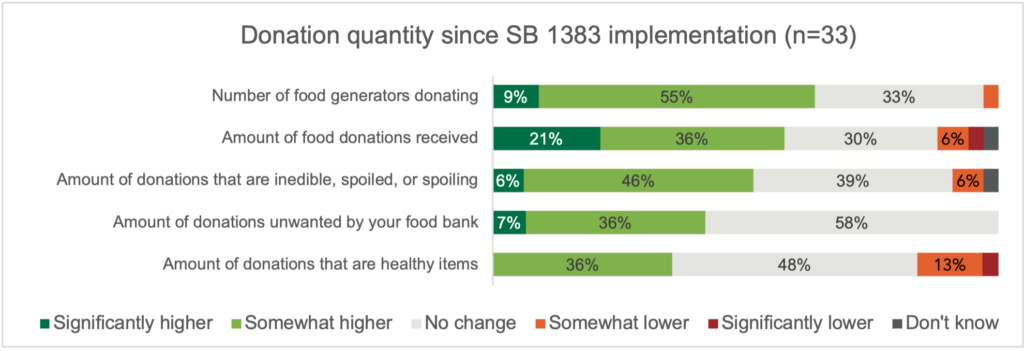

On the positive side, nearly two-thirds of food banks reported receiving more donations in recent years compared with before SB 1383 went into effect. Some were receiving more donations of nutritious items, like meat, produce, and dairy – which are particularly valuable because they are more costly for food banks to purchase.

On the other hand, not all of these changes were attributable to SB 1383, as some food banks were already seeing increases in donations before the law went into effect (due to their education efforts or other factors). Also concerning is that half of food banks reported receiving more inedible or spoiled food, which they must then dispose of themselves, incurring costs. And some food banks reported receiving less donated food overall, as food generators such as retailers have become more conscientious of their donation patterns and taken measures to decrease their own surpluses.

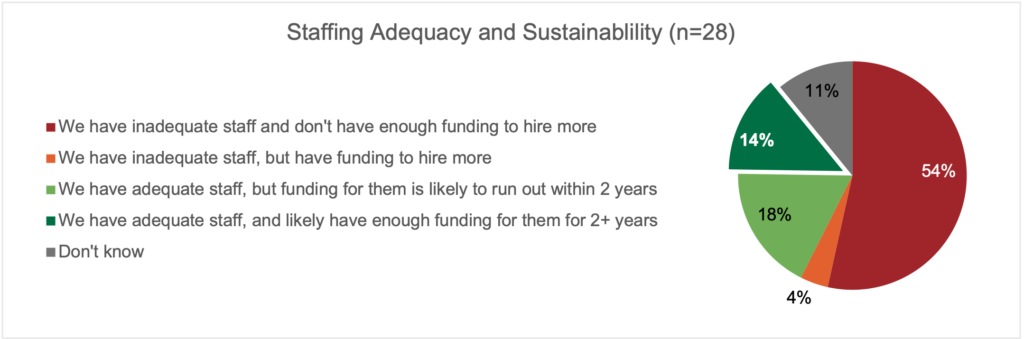

With food generators now required to find recipients for their surplus edible food, food banks reported spending more time establishing contracts to receive donations, educating donors and partner agencies, creating reports, and performing other administrative tasks. Half of food banks reported receiving some funding for food recovery, but not enough to cover their ongoing expenses. For example, two-thirds of food banks had to hire more staff members to support the additional workload, but most (75%) still reported they had inadequate staff or are likely to run out of funding within two years.

Moreover, food banks reported that insufficient infrastructure and staffing were significant barriers to maintaining and expanding food recovery work.

Food banks that stated that benefits outweigh costs were more likely to report:

Whereas food banks for whom costs outweigh benefits were those that reported:

We also found that food banks that reported receiving more donations since SB 1383 implementation were also more likely to report that they or their partner agencies had received fundingy their jurisdictions were more engaged in the process.

The extent to which SB 1383 works for food banks depends on a combination of factors, many of which are addressable – such as whether they obtained funding for food recovery and received healthier, better-quality donations from generators. The full report (link) contains more details about these and other important findings. We also list recommendations for different stakeholders in this complex food recovery ecosystem, on ways they can help maximize the effectiveness and long-term success of SB 1383.

Our evaluation of the early impacts of SB 1383 on food banks shows that funding and other investments are crucial for food banks to continue playing a key role in California’s progress toward climate goals while still fulfilling their core mission of improving food security.